Board games, AI, and real-world markets (part I)

Games have become a popular testing ground for reinforcement learning, as they require complex strategies to successfully play and win. Whether board games, such as AlphaGo, or computer games, such as StarCraft, different games offer diverse challenges for artificial intelligence.

Typically, the goal is to design and train a model that can outperform highly-rated human players at a deterministic game. That means, the game has no source of randomness and the outcome is determined solely by players’ actions. However, introducing randomness, or risk, can notably change player strategies. For example, an attacking chess piece will conventionally always win a confrontation. However, a player’s strategy would change considerably if an attach only had a 70% probability of success. Aggressive strategies now come with an inherent risk that must be weighed against the potential benefits of an attack.

Randomness, e.g. through dice rolls, can be used to simulate the complex dynamics of competitive markets, where not all parameters may be known or measurable. The strategies that AI models develop to deal with this randomness in turn serve as proxies for decision-making strategies in real-world scenarios.

This risk and the strategies AI models develop to deal with it are an ideal proxy for decision-making processes in real-world scenarios.

This project aims to understand the decision-making process in a competitive market with limited resources. The proxy for this scenario is the board game Camel Up by Pegasus Spiele. The core mechanics of the game involve placing bets on camels on a race track. The game is divided into ‘rounds’, in which each of the camels are moved a random number of spaces and in a random order. Dice rolls determine which camel moves and how far. The camel race is separated into rounds, consisting of a single move for each camel. That consequently means that each camel must move once before any can move again.

During this ongoing race, players can choose one of four actions each turn:

- move a random camel along the track by rolling dice (the player has no control over which camel moves beyond the limitation that each camel must move before they can move again),

- place traps to impede or help camels that land on them,

- make a bet on which camel will be furthest along at the end of the current round, or

- make a bet on which camel will win or lose the entire game.

The game’s difficult stems from the fact that camels can stack on top of each other if they land on the same space. If a camel is moved, all camels on top of it in the stack are also moved. This adds a layer of complexity to the game that makes it nearly impossible to predict which camel will win the race, or even the current round.

In the first part of this series, I will introduce my implementation of a digital version of Camel Up.

Simulating Camel Up

This project was inspired by Tyler Barron’s Camel Up Cup 2k18 and his code was used as a basis for this implementation. However, the code was buggy and/or incomplete and lacked the flexibility I wanted, so I dramatically expanded it and created what appears at first glance to be a rewrite with a number of “plagiarized” code blocks. For this reason, this code is published under the same open-source license as Tyler’s original project.

The full code base can be found on my GitHub repository.

The rest of this post will discuss the code in detail and make references to file names as they appear in the aforementioned repository. I assume the reader knows the rules of Camel Up.

This game is implemented in Python to later make use of the extensive machine and deep learning tools available for the Python programming language.

Components

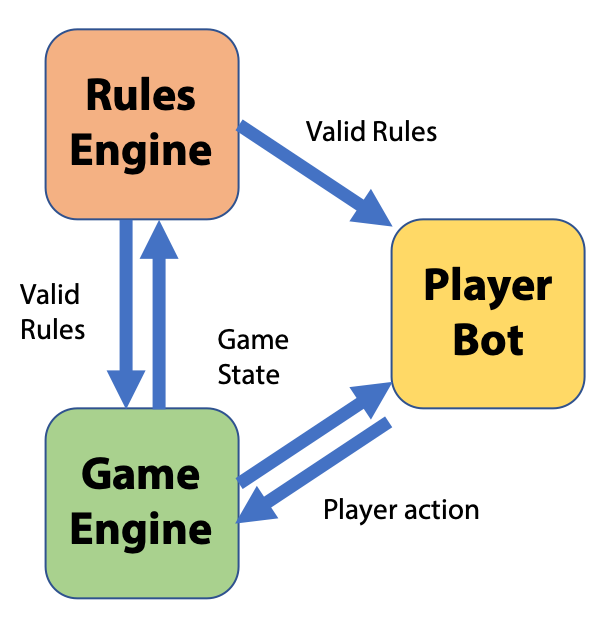

My implementation consists of three components:

- Game engine: keeps track of player actions and the current game state,

- Rules engine: determines which actions are permissible and which are forbidden based on the current game state,

- Player bots: decide, on the basis of the current game state, which actions to execute.

Upon a player bot’s turn:

- The game engine requests an action from a player bot by passing the current game state to the bot.

- The player bot requests a list of all valid actions from the rules engine.

- On the basis of its internal logic, it chooses an action to perform and communicates this to the game engine.

- The game engine requests a list of all valid actions from the rules engine and ensures that the bot’s chosen action is on this list.

- The game engine updates the game state and requests an action from the next player bot (repeat step 1 with the next player bot).

The double validation of rules ensures that no bot can cheat and potentially break the game state, making this engine suitable for tournaments and unsupervised play.

Player Bots

Player bots are implementations of a simple API. Each bot consist of a single custom Python class that extends the PlayerInterface class. This class must implement a single method, move(), which communicates to the game engine what action to take in the form of a return value. This method should take two parameters, the ID of the active player (as bots don’t know the ID that the game engine allocates), and a (deep) copy of the current game state. The permitted return values must be one of:

| Return Value | Description |

|---|---|

(MOVE_CAMEL_ACTION_ID, ) |

Move a camel |

(MOVE_TRAP_ACTION_ID, trap_type, trap_location) |

Place a trap |

(ROUND_BET_ACTION_ID, camel_id) |

Make a bet on the round winner |

(GAME_BET_ACTION_ID, bet_type, camel_id) |

Make a bet on the game winner or loser |

The first elements of each tuple are defined in actionids.py and serve to ensure compatibility with future versions. The simply correspond to the integers 0 to 3.

To ensure error-free execution, it is advised to use the get_valid_moves() function to obtain a list of permissible actions. For an example on how to create a custom player bot, see the abstract superclass playerinterface.PlayerInterface as well as bots.RandomBot, which randomly selects an action to perform.

class RandomBot(PlayerInterface):

"""

This bot randomly choses a move to make. It chooses in a hierarchical fashion, i.e.

1. Identify which types of moves are available

2. Choose a type of move, i.e. move camel, place trap, make a game bet, or make a round bet

3. Randomly select the specific variant of the move to perform, e.g. where to place the trap and what kind it should be.

"""

@staticmethod

def move(active_player, game_state):

valid_moves = get_valid_moves(g=game_state, player=active_player)

valid_super_moves = tuple(set([move[0] for move in valid_moves]))

random_super_move = random.choice(valid_super_moves)

possible_moves = [move for move in valid_moves if move[0] == random_super_move]

return random.choice(possible_moves)

Player bots can see the current game state as well as all permitted rules. However, as the rules state that game winner and loser bets are secret, the bots are not given this information by the game engine. The engine achieves this by passing a modified (deep) copy of the game state to a player bot in which all game bets not made by the active player are set to (None, None), i.e. the player bot will know how many bets were made but it will only know the details of the bets it made.

WARNING: Python is not designed to be a “secure” programming language in that it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to obfuscate the values of variables at runtime. A clever programmer will most likely be able to bypass the relatively simplistic security measures put into place to hide game bets. If this code is ever used in a tournament setting where cheating is to be avoided, manual inspection of the bot code is absolutely necessary. Rest assured, though, cheating will require programming tricks that an AI bot will not learn.

Diving into the Code

I’ve made a point of documenting the code base very thoroughly, so this post will only include snippets of code. It will be easier for you to clone the repository to your computer and view the code in an IDE of your choice alongside this post.

Game Engine

The core file of the repository is camelup.py, which contains the code for the game engine as well as the rules engine. The former consists of the game state, functions to adjust the game state according to the game rules, and some auxiliary functions.

The ‘GameState’ class contains all the data that the program needs to persist. This includes immutable global parameters, like the number of camels or the board size, and mutable game state variables that describe the current situation of the board, including the current position of the camels, the bets placed, and the amount of money each player has. As a development aid, the global parameters are all in capital letters and the overwritten __setattr__() function ensures that they cannot be changed after the game state has been initialized. As before, this does not constitute an actual security measure that cannot be circumvented.

Of note is the function get_player_copy(), which creates a deep copy of the game state object but obfuscates the game winner and loser bets so that only those made by the current player remain visible.

The core game mechanics are encoded in the following functions:

play_game(...)- Simulates a single game. It does this by creating a new

GameStateobject and then iterates through the players, letting each one perform an action in turn. This function is primarily responsible for checking the validity of the moves by comparing the action returned by a player bot with the list of valid actions as given by the rules engine. If the move is valid, thenplay_game.action(...)executes one of the four action methods,move_camel(...),move_trap(...),place_game_bet(...), orplace_round_bet(...). The game continues until theGameStateobject itself decides that the game is over by setting its attributeactive_gametoFALSE. This is conventionally done when a camel reaches the end of the board.

- Simulates a single game. It does this by creating a new

move_camel(...)- Initiates a camel move. The function will select a random camel (from a uniform distribution) that hasn’t moved in the current round and roll the dice to determine how far the camel may move. The function then tests whether a camel hits a trap and if it does, alters the move and stacking behavior accordingly and pays out the player who set the trap. Lastly, the player who initiated the move is paid out as well and the camel moved to its new position. If it only moved forward, it will be placed at the top of the camel stack it lands on but if it landed on a -1 trap and moved backwards then it will be placed at the bottom of the stack.

move_trap(...)- Places, or moves, a player’s trap. The function automatically decides whether to place or move the trap based on whether the player has already placed their trap.

place_game_bet(...)- Places a bet on the game winner or loser.

place_round_bet(...)- Places a bet on the round winner.

end_of_round(...)and ‘end_of_game’- Triggers the logic at the end of each round, i.e evaluate round winner bets, and the end of the game, i.e. evaluate the game winner and loser bets and determine the game winner.

Rules Engine

The “rules engine” is encapsulated in a single function, get_valid_moves(...), which simply determines all legal moves for a given player based on the current game state. This function takes all of the game rules into consideration and should be the final authority in whether a move is legal or not.

Running the Game

The file rungame.py contains boilerplate code to run the game. To simulate games, execute the command python rungame.py <NUM_GAMES> <PLAYER_1> ... <PLAYER_N> from the command line, where NUM_GAMES is an integer indicating how many games should be simulated and PLAYER_1, …, PLAYER_N are the names of the player bots to set as players. Bot names must be the names of classes in the bots.py file.

For example, the command python rungame.py 100 RandomBot RandomBot RandomBot RandomBot would therefore simulate 100 games between four identical players (initialized from bots.RandomBot), whose strategy is to select a random action from a uniform distribution.

Game Logs

The game logs are stored as CSV files in the directory game_logs. At the moment, game logs have the following column structure:

| Column | Description |

|---|---|

| active_player | The player who performed an action during this round |

| bet_type | If the player made a game bet, was it a bet on the winner or loser? |

| camel | What camel was moved or bet on |

| camel_<CAMEL_ID>_location | The current location of camel with the name |

| camel_<CAMEL_ID>_stack_location | The current location of camel with the name |

| distance | How far was the camel moved? This is the net distance, i.e. if the camel landed on a trap then this is taken into consideration |

| player_#_coins | How many coins a player has |

| player_#_trap_location | Where the player’s trap is on the board |

| player_#_trap_type | Whether the player has set his trap to +/- |

| round_id | The number of the current round (one player action constitutes a round) |

| trap_location | Where a player placed his trap if he placed it in this turn (this is technically redundant with player_#_trap_location) |

| trap_type | Whether a player placed a +/- trap if he placed it in this turn (this is technically redundant with player_#_trap_type) |

This format may change in the future, though. The GitHub repository will always provide the most up-to-date description.

Initially, every game will be stored in a separate log file named game_#.csv. A helper script, merge_game_logs.py can be used to merge these individual logs into a single CSV file by simply running python merge_game_logs.py <LOG_DIRECTORY>.

In the next installment of this series, I will take an initial look at the game itself to begin building hypotheses about successful strategies. For example, does the initial placement of a camel at he beginning of the game influence the final standing?